The feminist movement has a long and complex history. Ever since the late 19thcentury, women have fought for equality, starting with the suffragette movement and getting the right to vote, leading all the way to today’s Pussyhat Project. Throughout the decades, feminists have advertised their movement using design, trying to raise awareness and to express their mission of making the world a better place. But how does feminism in design affect the movement – and who benefits from it?

If you walk around London these days, it seems as if feminism has become an inherent part of advertising. Brands are trying to position themselves as official advocates for equality and make use of the current popularity of the feminist lifestyle, suddenly aiming to support women in all kinds of different ways. This so called femvertising is becoming a more and more popular tool for brands to promote themselves with, and consequently, feminism in design has gained more relevance than ever.

What does design do?

Before talking about feminism in design, we should talk about design in itself. There are many different types of design – graphic design, web design, product design, to name a few – and they all serve the same two main objectives: meeting the client or the target group’s needs and wants, and constant improvement. Design aims to meet and exceed expectations, always being a better version of what was before. It is constantly around and has a huge influence on how we see our world.

Design can, however, also be discriminatory, especially when it comes to gender. Certain colours, fonts and imagery are associated with male or female, and not conforming to this standard is perceived as being bold or even brave. Imagine a brand like Lynx would use a pink, twirly font in their marketing campaign for a new deodorant scent for men – it would take the essence of their whole campaign, which is men making women go crazy by smelling very masculine, away. A whole campaign would collapse because of the font and colour chosen to promote the product. The image of the brand would shift from being cool and young to being inexplicable and probably making the consumer feel a bit uneasy.

Of course, gender stereotypical design has improved over the past decades. The rules are not as traditional as they used to be, and brands are becoming braver in their approach. And this is where feminism comes in.

Feminism as a lifestyle

Feminism hasn’t had a purely political core for a long time. The term feminism has shifted from describing an important equal rights movement lead by mainly women to serving as a brand people choose to define their lifestyle. Suddenly everyone wears T-shirts with GIRL POWER printed on them, people state in their Instagram bio that they are a feminist and post pictures of their stretchmarks, explaining how beautiful they are to them. Not only is this missing the point of feminism, but it is also throwing a shadow over the actual movement genuinely concerned activists are trying to advance.

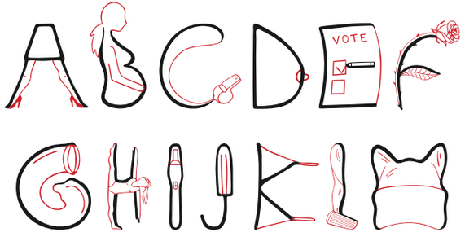

Designers have jumped onto this trend and started feeding the demand for feminist lifestyle content. There are fonts that integrate certain feminine features or objects, posters that show feminist symbols or fashion items that state allegedly feminist slogans. (The future is not only female!). There is stationery and jewellery, candles and water bottles that state some sort of feminist message, and people are proudly carrying those items around as a way to visualise certain character traits.

Arguably, not every feminist design is made to serve as a part of this pop cultural trend. Most feminist institutions make use of some sort of design, if only for a logo or a web site. Posters are made for marches, leaflets and stickers to spread awareness and gain attention. Even some artists, such as Barbara Kruger, for example, have used feminism in their art to raise awareness of patriarchal oppression or the feminist movement, montaging statements with a feminist message onto black and white photographs or prints. In her case, everyone benefitted from this: the statements on her collages were direct and unapologetic, underlining the importance of change and gender equality and are still used today to raise awareness, but she also gained fame as an artist by using feminism. The difference to this appropriation of the political issue and the The Future Is Female shirt is, however, that the purpose of the design in Kruger’s case seems to serve women collectively, whereas the shirt only serves the individual and their own presentation.

Feminism in Design – can it be both?

However, there is, as so often, an area between these two extremes. When Donald Trump called Hillary Clinton a “nasty woman” on American national television during the third presidential debate, it didn’t take long until “nasty woman” merch was available to buy everywhere on the internet. Shirts, necklaces, hats, key rings – all with differently designed variations of the same two words printed onto them. Undoubtedly, the sellers of these items are likely to have had their financial profit in mind rather than actually wanting to point out the problem with misogynist statements about powerful women, but nevertheless, it helped this small but profound statement to get the relevance it deserves. It was not just quickly mentioned by the newspapers and then forgotten – design helped it to be recognised as what it is: a typical reaction of people who feel uncomfortable with women who take control, trying to bully them into backing off. Design made this example of female oppression timeless and helped reminding the public on how easily these things are said about women, and consequently, underlining the urgency for change.

It is therefore safe to say that design can bring advantages to feminism and other political movements, if it aims to achieve the right goal. There is a fine line between raising awareness, being supportive and empowering women, and co-opting the message in order to create demand for your brand. Looking at the purpose of each individual design that claims to be feminist is therefore a good practice for everyone interested in supporting the movement – after all, most designs do raise a little bit more awareness to the issue, even if the brand and the individual consumer are the ones that benefit the most.